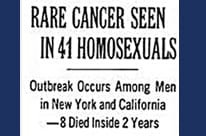

On July 3, 1981, a now-famous New York Times article carried the headline, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The article described the sudden appearance, in gay men from New York and Los Angeles, of a rare skin cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Previously, this cancer had been known to affect primarily elderly men of Mediterranean and Jewish descent, who might live for many years with the disease. Now, it was occurring in otherwise young, healthy men with deadly consequences. This was the first announcement, in the mainstream press, of what would become the AIDS epidemic.

Often appearing as bright purple spots, KS lesions were one of the main symptoms for which the affected individuals sought help from doctors. About 50% of AIDS patients in 1981 had KS as their presenting symptom. Doctors, having few other options at their disposal, often treated their new cancer patients with chemotherapy.

Often appearing as bright purple spots, KS lesions were one of the main symptoms for which the affected individuals sought help from doctors. About 50% of AIDS patients in 1981 had KS as their presenting symptom. Doctors, having few other options at their disposal, often treated their new cancer patients with chemotherapy.

It would not be long before AIDS shed its link to cancer, as opportunistic infections eclipsed KS as the major sign of the condition, and as scientists began to understand both as resulting from a mysteriously crippled immune system. But this early connection to cancer had far-reaching implications for the course of the epidemic. Coming at a time when cancer was viewed as the nation’s number one health crisis, AIDS initially attracted attention—when it attracted attention at all—from researchers hoping to understand cancer.

“What we can learn from this group of individuals about cancer in general—how it’s transmitted, what causes it, hopefully how to stop it—is absolutely unbelievable,” said Marcus Conant, MD, a physician in San Francisco who treated some of the earliest AIDS cases, in a June 1982 CBS interview.

The epidemic of cancer among gay men seemed to suggest that cancer might have a traceable cause—one that, if identified, could help lead to a cure for cancer in general. That didn’t happen. Nevertheless, it was cancer research—much of it funded by the Cancer Research Institute (CRI)—that laid the foundation for our understanding of AIDS. Without this research on cancer, it’s likely that scientists would not have discovered the cause of AIDS when they did.

The Hunt for Cancer Viruses

To fully appreciate the role that cancer played in AIDS, we have to go back to the 1960s, when researchers became convinced that cancer had a viral cause. A viral cause of cancer was first proposed back in 1911 by a biologist named Peyton Rous at the Rockefeller Institute, who provided strong evidence that a virus transmitted cancer in chickens. But the wider scientific community was skeptical, and his research was largely ignored for the next 50 years. It was not until the 1960s that interest in the idea of cancer viruses really took off, following the discovery by Ludwik Gross at the Bronx Veteran Affairs Medical Center that viruses can cause leukemia in mice. (See Timeline of Progress.)

These discoveries unleashed an explosion of research. In 1968, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) inaugurated its Special Virus Cancer Program, with the goal of identifying human cancer viruses similar to the ones that cause cancer in chickens and mice. The hope was that by pinpointing cancer viruses in humans it would be possible to vaccinate against them and prevent cancer. Despite more than a decade of research, however, the effort largely failed, and by the late 1970s, many researchers had soured on the idea. When the program was terminated in 1980, a medical consensus had emerged that viruses were not a significant cause of human cancers.

Enter AIDS. The rising tide of Kaposi’s sarcoma, known colloquially as “gay cancer,” breathed life back into the cancer virus paradigm. Suddenly, cancer was appearing in clusters of interlinked people, suggesting that a transmissible biological agent, such as a virus, was the cause.

“Cancer is not believed to be contagious,” wrote New York Times reporter Lawrence Altman in the 1981 article. “But conditions that might precipitate it, such as particular viruses or environmental factors, might account for an outbreak among a single group.”

Because viruses were known to cause cancer in some laboratory animals, it was a natural step to suspect a virus in these human cases. And sure enough, people with AIDS were found to be infected with quite a few different viruses, including cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, and herpes. But these garden-variety viruses were nothing new. Why would they start causing an epidemic of cancer now?

“I sincerely doubt that anyone would have been looking for a retrovirus as the etiological agent for AIDS had HTLV-I not previously been isolated.” — Anders Vahlne

Among the few scientists still pursuing cancer virus research at this time was Robert Gallo, MD, of the NCI. Gallo had been searching for viral causes of cancer since the early 1970s, when, as a practicing oncologist, he became interested in the causes of childhood leukemia. Even after the intellectual tide turned against him, he continued to work on the topic. In 1980, Gallo’s persistence paid off. He discovered a virus, which he named human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV-I), that was linked to a rare form of lymphoma in people. As its name suggests, the virus was specific for immune cells called T cells, which it infects and causes to replicate uncontrollably. Not only that, the virus was a retrovirus—the same sort of virus that Rous and Gross had found causes cancer in animals, and which had prompted the search for human cancer viruses in the first place. (Retroviruses are viruses that convert their RNA-based genetic material into DNA using the enzyme reverse transcriptase; the viral DNA is then inserted into the DNA of the host, where it is copied to make more viruses.) This work was followed the next year, by the discovery of a second human retrovirus, HTLV-II, linked to a different cancer. These were the first cancer-causing retroviruses to be discovered in humans.

Gallo began thinking about a retroviral cause of AIDS in 1982, after hearing a talk about the epidemic from researchers at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). At this time, there were at least a dozen different theories of AIDS causation, including drug use and other non-infectious causes. But Gallo was bolstered in his thinking about retroviruses by his previous discoveries.

Gallo began thinking about a retroviral cause of AIDS in 1982, after hearing a talk about the epidemic from researchers at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). At this time, there were at least a dozen different theories of AIDS causation, including drug use and other non-infectious causes. But Gallo was bolstered in his thinking about retroviruses by his previous discoveries.

Just two years later, in 1984, in the pages of Science, Gallo presented evidence that a newly identified retrovirus was the cause of AIDS. That virus, which Gallo called HTLV-III, had first been spotted in cells from an AIDS patient the previous year by Luc Montagnier, MD, and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, PhD, at the Pasteur Institute in Paris (work for which they won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine). Gallo clinched the case for this virus being the cause of AIDS by showing that antibodies to the virus were found in the blood of 48 patients with AIDS or pre-AIDS but not in healthy controls; that the virus could be detected in semen of people with AIDS; and that the virus could be isolated from T cells obtained from AIDS patients.

The discovery of the causative virus, renamed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), was a major milestone in the epidemic, paving the way for a blood test and a way to screen blood donors. But it was cancer that laid the foundation.

Both Gallo and Montagnier were able to make their discoveries thanks to Gallo’s previous research on T cell cancers. It was through that cancer research that Gallo’s lab identified the primary growth factor for T cells, called interleukin-2 (IL-2). Without IL-2, it would not have been possible to grow T cells in culture long enough to isolate the AIDS virus. Moreover, before Gallo discovered HTLV-I, there were no known viruses that specifically targeted T cells, the same cells that are depleted in AIDS.

“I sincerely doubt that anyone would have been looking for a retrovirus as the etiological agent for AIDS had HTLV-I not previously been isolated,” wrote Anders Vahlne, a virologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, in a 2009 historical reflection.

That’s not the end of the cancer connection. It was cancer research that helped to explain how a retrovirus might be able to cause both cancer and immunodeficiency—a seeming paradox at the time. After all, the previous retroviruses that Gallo had discovered cause T cells to multiply uncontrollably (i.e., they cause cancer), whereas whatever was causing AIDS caused T cells to die. A retroviral cause of AIDS only makes sense when you put it in the context of other research, on animal cancers, much of it spearheaded by CRI scientists.

“Fading Kitten Syndrome”

Former CRI medical director Lloyd J. Old, MD, had a longstanding interest in animal cancers. In 1975, with funding from CRI, he helped establish The Donaldson-Atwood Cancer Clinic of the Animal Medical Center in New York, which to this day specializes in treating animals with cancer. Old believed that important lessons about human cancer could be learned by studying cancer in animals, and this was just one way in which he supported this effort.

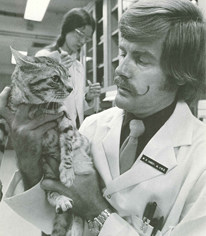

In 1969, Old hired a newly minted veterinarian from the University of Pennsylvania to do a postdoctoral fellowship in his lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering. That postdoc, William Hardy, D.V.M, PhD, was interested in studying a newly discovered retrovirus, called feline leukemia virus (FeLV), which caused cancer in cats. In particular, Hardy was interested in understanding how the retrovirus is transmitted.

In 1969, Old hired a newly minted veterinarian from the University of Pennsylvania to do a postdoctoral fellowship in his lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering. That postdoc, William Hardy, D.V.M, PhD, was interested in studying a newly discovered retrovirus, called feline leukemia virus (FeLV), which caused cancer in cats. In particular, Hardy was interested in understanding how the retrovirus is transmitted.

“The dogma at the time was that these types of viruses, in the mouse and chicken, were all transmitted vertically—inherited in the egg and passed down from one generation to the next,” says Hardy. “You didn’t catch them contagiously.”

But Hardy knew of cases where households of unrelated cats seemed to “come down” with cancer, as well as other anecdotal evidence suggesting a contagious cause, so he decided to address this question directly.

Using a blood test he developed with funding from CRI, Hardy showed that unrelated cats living with at least one cat with a type of cancer called lymphosarcoma had a much higher likelihood of harboring FeLV themselves. Moreover, these FeLV-positive cats were 900 times more likely to develop cancer than they would have otherwise. This work, published in Nature in 1973, was the first to show that a cancer-causing virus could be spread ‘horizontally’ through close contact—in this case, through blood and saliva.

At that point, he says, “all hell broke loose,” because people didn’t believe that these viruses could be spread horizontally. But the results proved sound, and eventually allowed the researchers to develop a vaccine for the virus—the first vaccine to prevent a naturally occurring cancer.

In addition to causing cancer, FeLV was also known to cause something called “fading kitten syndrome,” an immunodeficiency that caused cats to waste away. In fact, says Hardy, more cats die from the immunosuppression effect of the virus than they do from cancer. As a few perceptive researchers noted at the time, this syndrome in cats looked a lot like AIDS in people.

“We started calling it FAIDS,” Hardy says. “For feline AIDS.”

Among the first to make this intellectual leap was a young researcher named Don Francis, MD, D.Sc. who had pursued his doctoral work on FeLV in the lab of Max Essex, D.V.M, PhD, at Harvard. Essex had been a close collaborator of Old and Hardy’s; he is a co-author on the 1973 Nature paper. Francis wanted to know whether FeLV could be transmitted from cats to their human owners—and therefore, might spread cancer to them. Fortunately, this turned out not to be the case, but Francis’s work on FeLV left an indelible mark on his thinking.

When the AIDS crisis began, Francis was working as a field agent for the CDC in Arizona. He had previously studied hepatitis B in the gay male community, and the CDC now tapped him to investigate the new cluster of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia being reported in gay men.

“This is feline leukemia in people.” – Don Francis

Passionate and outspoken, Francis quickly established himself as one of the most important investigators of the early AIDS epidemic. His efforts to uncover the cause of the disease form the central story of the movie And the Band Played On (1993), based on the 1987 book by Randy Shilts. Francis (played by Matthew Modine in the film) and his colleagues at the CDC gathered the first persuasive evidence suggesting that AIDS was a sexually transmitted disease. In particular, they noted that the transmission patterns and affected groups seemed to mirror those of hepatitis B, a blood-borne virus.

But Francis also had a theory of what might be causing the disease—a retrovirus, much like FeLV. “This is feline leukemia in people,” Francis reportedly said to his old mentor, Max Essex, on the phone one day in June in 1981. He was thinking of the work that Essex and Hardy had done on the immunosuppressive aspects of FeLV.

Gallo, too, had gotten the idea to link retroviruses and AIDS from research on FeLV, through conversations with William Jarrett, PhD, the discoverer of FeLV, as well as Essex and Hardy. And all of these researchers—Old, Hardy, Essex, Jarrett, Gallo, Montagnier, and Francis—were interested primarily in understanding the role viruses play in cancer.

An Early Ally in the AIDS Epidemic

Perhaps because it was seen as a disease of homosexuals and drug addicts, funding for scientific research into the causes and treatment of AIDS was not immediately forthcoming from the U.S. government. In a letter to his superiors at the CDC, Don Francis wrote in April of 1983, “Our government’s response to this disaster has been far too little…The inadequate funding to date has seriously restricted our work and has presumably deepened the invasion of this disease into the American population.”

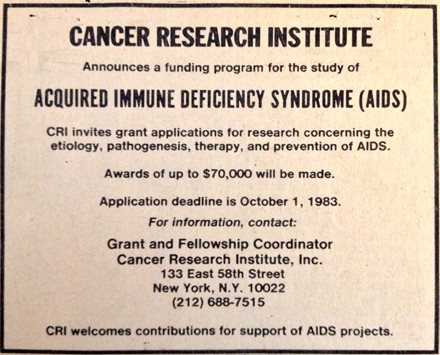

CRI’s leadership recognized early on that AIDS warranted research funding, and stepped in to fill the void. If immunocompromised people were getting cancer, then that must be because the immune system normally functions to keep cancer in check, and CRI scientists were keen to understand that link.

“AIDS is a major concern and a major mystery—a compelling problem that merits a special CRI program.” – Lloyd Old

In February 1983, CRI provided crucial funds to support an important meeting on AIDS and Kaposi’s sarcoma, held at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. The meeting was organized by Bijan Safai, D.Sc., an expert on Kaposi’s sarcoma at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and now a member of CRI’s Scientific Advisory Council. Safai says he was prompted to convene a meeting because there was so much chaos in scientific thinking at the time, between oncologists trying to cure cancer with chemotherapy and molecular biologists looking for cancer-causing oncogenes.

“I said, ‘Can we do a Cold Spring Harbor meeting and bring everyone together to put some sense into this epidemic?’”

The meeting was planned and all the “big brains” in science were invited, but it was kept strictly confidential. No public announcement was made and the media were never informed.

“We were afraid that people wouldn’t speak their minds, feel free to speculate, and speculation was one of the very few tools we had,” says William Topp, PhD, at the time a senior scientist at Cold Spring Harbor who co-organized the meeting and who approached CRI about funding.

The meeting achieved its goal. It was attended by many of the world’s leading virologists and oncologists, and it was at this meeting that many important hypotheses were discussed, including the one that would ultimately prove decisive.

“That was the first time people talked about a retrovirus,” recalled Clifford Lane, MD, an NIH scientist who attended the landmark meeting.

Later that same year, in June of 1983, CRI allocated $350,000 for new research projects devoted to AIDS. Then medical director Lloyd J. Old said at the time, “AIDS is a major concern and a major mystery—a compelling problem that merits a special CRI program.” Among the researchers funded was Dr. Safai, who was given $50,000 to study interferon as a treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma. This project was co-funded by both CRI and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), at the behest of activist and author Larry Kramer.

Dr. Safai played a more influential role in the epidemic than many people realize. In addition to organizing the meeting noted above, he also contributed to the research that led to the discovery of the HIV virus. It was blood from his Kaposi’s sarcoma patients in New York that Gallo’s lab used to identify the HTLV-III virus and led to the development of the ELISA diagnostic test for HIV.

“The first 100 patients tested were my 100 patients,” says Safai. “That was the first AIDS test in the world.”

Dr. Safai says his involvement in the epidemic was largely accidental, a product of his being one of the few researchers working on Kaposi’s sarcoma at the time the AIDS epidemic hit. In 1980, he had published an important paper on KS that argued that the cancer was likely caused by a virus, and was linked to immunodeficiency—emerging when the immune system was compromised, as sometimes occurs after organ transplants, for example. “Suddenly I started to get phone calls from the United States and Europe, asking me all these questions, and that’s why I ended up being in the middle of this epidemic.”

He says he started collaborating with Gallo because he suspected early on a retroviral cause of AIDS and learned from his colleague William Hardy (the feline leukemia expert) that Gallo was the one person who could culture it. “Hardy’s the one who said, ‘Gallo has the lab and the technology to solve it.’”

Initially, Safai thought that whatever virus was causing AIDS was also responsible for producing KS. But eventually it would become clear that two viruses were at work—one causing immunodeficiency, and one causing KS. The virus causing KS (herpesvirus-8) was eventually discovered in 1994.

Dr. Safai remembers that time as incredibly exciting, but also frightening. “Because we knew there was a virus, but we didn’t know how it was spread. So, there was always a chance, every minute of the day, that we could become infected.”

Dr. Hardy as well recalls that period as a stimulating one, and especially values the many years he worked as a colleague with Lloyd Old. “I don’t think Dr. Old has gotten his due on the retrovirus work,” says Hardy. “He was a pioneer in the field.”

We now know that viruses cause roughly 10%-15% of human cancers, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, liver cancer, and cervical cancer. Vaccines to prevent some virus-caused cancers now exist, including Gardasil, the cervical cancer vaccine, which was developed by immunologist Ian Frazer with funding from CRI. Undoubtedly, these developments owe a debt to the cancer-virus paradigm, which AIDS helped to rekindle.

And yet, most of the major cancer killers—lung, breast, colon—are not known to have a viral cause. Moreover, retroviruses are known to cause only a very small fraction of human cancers, unlike the situation in animals. Thus, the great breakthrough in cancer presaged at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic did not come to pass.

“The arrival of AIDS helped us to think more and more of viruses causing cancer,” says Safai. “But even 30 years later, there’s still very few viruses shown to cause cancer.” Ultimately, cancer did more for AIDS than AIDS did for cancer.

“The arrival of AIDS helped us to think more and more of viruses causing cancer,” says Safai. “But even 30 years later, there’s still very few viruses shown to cause cancer.” Ultimately, cancer did more for AIDS than AIDS did for cancer.

CRI was there at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, but its involvement didn’t end there.

Recognizing the truly global nature of the epidemic, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, CRI became a steady funder of AIDS research in Africa, supporting several international symposia.

And since that time, CRI has provided nearly $6 million in funding to more than 50 researchers studying HIV. Work from these researchers has provided us with an evermore sophisticated understanding of how HIV acts to disrupt the immune system, paving the way for improved treatments not only for HIV, but also for cancer, allergies, and other immune-related diseases.